Welcome to the adolescent brain. I’m your host, an Outward Bound Instructor. I specialize in working with students and their families on Intercept courses, and help students learn positive decision-making skills and practice building positive relationships. My goal is to make the transition home, after an Intercept course, smooth as possible and help families apply what their child learned on Intercept to their daily lives.

On Intercept courses, students focus on learning positive decision-making skills, building positive relationships and using positive coping skills.

A Breakdown of the Brain

Hold up your hand as if you’re taking an oath. Consider your wrist the brainstem. This is your “reptilian brain,” which performs automatic functions like breathing, digestion and regulating heart rate and body temperature, etc.

From there, fold your thumb over your palm as if you’re holding up the number “four.” Consider your thumb the amygdala, or your “mammal brain,” which is responsible for our emotions and feelings.

Finally, fold your four fingers on top of your thumb creating a closed fist. Consider those folded fingers the prefrontal cortex, or your “human brain,” which is responsible for sifting through thoughts, determining potential consequences, working toward goals and controlling social behavior.

Because the brain develops at the brain stem first, the emotional amygdala next, and the logical prefrontal cortex last, teenagers are more likely to act on raw emotion than rational judgment. The prefrontal cortex and the impulse control that comes with it aren’t done developing until around age 25.

What Happens in the Adolescent Brain

For example, let’s look at the song “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” You get it right every time it pops into your head. It’s a simple and satisfying tune.

However, it becomes far more complicated when someone throws in some Christina Aguilera-style runs, whistling, humming and instrumentals. The complexity increases when the key and lyrics change, and the parts overlap in an endless cycle; the song grows in volume and takes on an interpretive dance number; parts of the song are disappearing and there’s someone running around, screaming, crying, laughing, playing and fighting.

What just happened?

Metaphorically, version one of the song is an adult’s brain. It’s streamlined and predictable. Version two is an artist’s rendition of an adolescent’s brain. It’s chaotic and confusing. Essentially, the standout characteristics of the pre-teen and teenage brain are: moody behavior, risky behavior, slowly erasing parts, addition of detail, connection, distraction and growth.

All of those characteristics were present in version two of “Row Your Boat.”

Moody & Risky Behavior. Three important neurotransmitters in an adolescent’s brain are:

- Serotonin: a mood stabilizer whose production decreases during adolescence.

- Testosterone: associated with anger and aggression. Production increases during adolescence.

- Dopamine: helps control the reward and pleasure systems in the brain. Production increases by partaking in risky behavior.

Slowly Erasing Parts. During adolescence, there are still large amounts of neurons that aren’t often used. These begin to die off in a process called “synaptic pruning.” This process makes the brain more efficient and specialized.

Addition of Detail & Connection. As we age from child to adult, sections of the brain connect so that the nervous system can function properly. Because these connections aren’t complete until adulthood, a teen’s brain literally isn’t fused together yet, making them more likely to act impulsively.

Distracted & Growing. Throughout adolescence, the brain is developing as fast as an infant’s brain. Different parts of the brain develop at different rates.

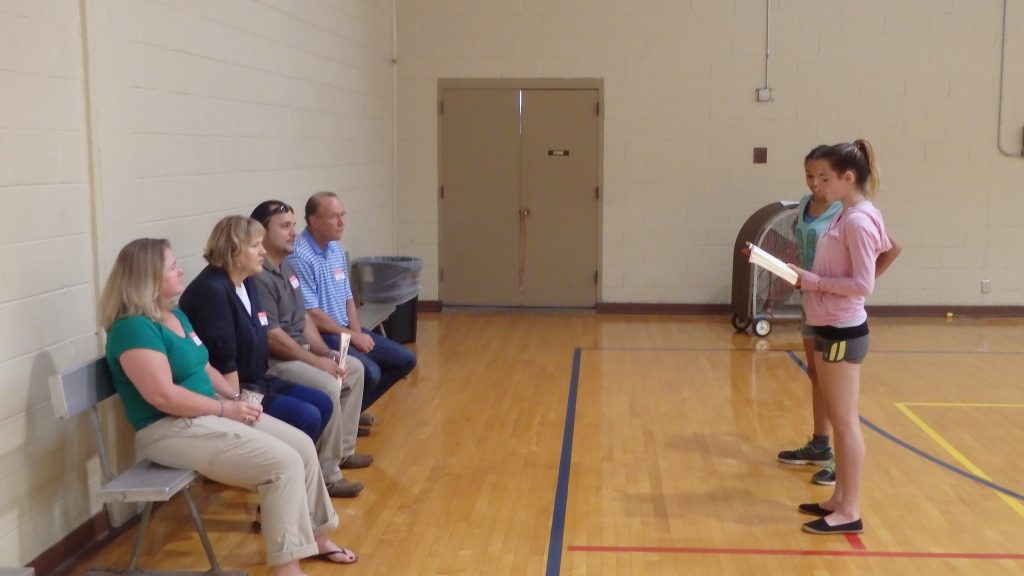

Outward Bound Intercept students create an environment of support with each other.

Strategies for Working with Adolescents

As an Instructor, it’s extremely fulfilling to work with teens and offer them the resources that their prefrontal cortex can’t yet provide.

Stepbacks and Visual Checklists

For example, because teens are typically emotionally-driven and impulsive, we offer what we call Stepbacks on Intercept courses. These are opportunities for a student to step away from the group and collect their thoughts in order to return in a more rational state of mind.

We also use visual checklists so that students can see how much they’ve accomplished and what they still need to do each day. To keep it top of mind, these visuals are written on a student’s water jug or on a canoe in chalk.

Structure and Consistency

Most importantly, we provide structure and consistency. Teens may not realize it without the help of a fully developed prefrontal cortex, but they want consistency. That’s why we always follow through with what we say we’re going to do in order to earn their trust and help them learn. For example, if we establish that we’ll be washing our bowls each night after dinner, then we’re going to follow through with that expectation despite rain, late nights or complaints. If a student doesn’t follow through, the natural consequence of ants in their bowl will speak for itself.

Photo by Rachel Veale.

Unconditional Positive Regard

When I consider how an adolescent’s brain is thinking at any given moment, I’m reminded to have unconditional positive regard for my students. I’m out in the field with students for anywhere from 20 to 28 days. In that time, pre-teen and teen students are likely to exhibit behaviors—such as cursing me out—that I could easily take personally.

Maybe my student is uncomfortable because she’s getting bitten by bugs and doesn’t have the logic to wear her bug clothes. All that she’s able to connect in her brain is that she’s upset, and I’m right there, so she cusses me out. And this may happen at home, too. Perhaps your teen is super moody in the morning after staying up playing video games until 2 a.m. He has an attitude with you when you remind him to pack his lunch for school. He can’t yet conceptualize that his tiredness is his own doing because he didn’t have the foresight to go to bed at a reasonable time. He can’t piece it all together—yet.

Teens act out over things that we can see aren’t worth having a bad day over. What I think must be challenging for a parent, and can be hard as an Instructor, is not to take that moodiness personally. My strategy is to practice rational detachment, which is defined by the Crisis Prevention Institute as, “the ability to manage your own behavior and attitude and not take the behavior of others personally.”

My rational detachment mindset has helped me manage a student’s hostility toward me as if I had summoned the bugs to bite them. If only I could control the mosquitos.

A Final Message

When your child is screaming at you from the passenger seat because you made him brush his teeth and get to school on time, please remember you can’t control the mosquitos. You can’t control what version of “Row Your Boat” is playing in your child’s head.

When I work with families at the end of an Intercept course and we talk about the adolescent brain, my hope is that we all walk away remembering that it’s important to be patient and avoid judgment. Teens are doing the best they can with the brains they have at this time in their lives. We can supplement them with tools to help them practice good judgment as they wait for their prefrontal cortexes to develop.

About the Author

Elizabeth Bowling is a field Instructor for the North Carolina Outward Bound School. She is based at the Scottsmoor, Florida basecamp and primarily instructs flatwater canoeing courses for at-risk youth which focus on behavior management. Elizabeth has a degree in journalism and international studies from the University of Connecticut.

OTHER POSTS YOU MAY LIKE

Read More

Read More

Read More