What began as a goal to beat a standing record, turned into a six-month journey of challenge and perseverance for Outward Bound Instructor Rachel Veale.

It’s 9 PM on a Saturday evening and I’m lying in bed. I pick up my phone from my bedside table and again review the to-do list I’ve written for the next day – April 4th, 2021.

In the morning:

Check Blue Ridge Parkway closures

Coffee

Try to eat

Put on watch

Write splits on arm

Pack resupply and post-run clothes in car

Meditate

Leave car keys on top left tire

*$%#ing crush it.

I click the phone shut, set it back on my table and attempt to settle into sleep.

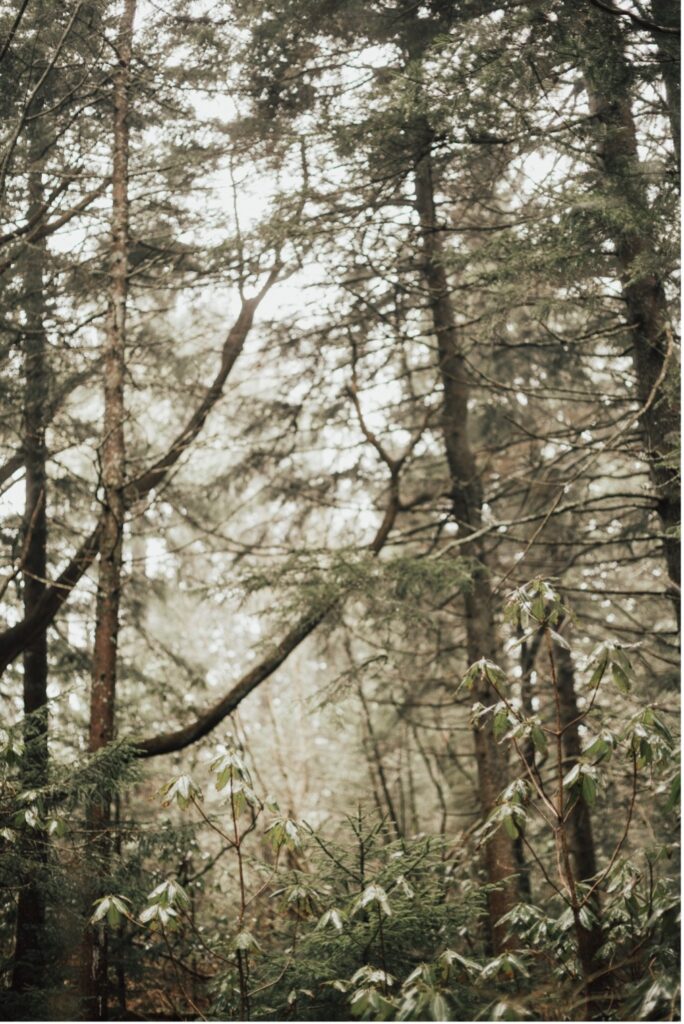

Rain-soaked rhododendrons in Pisgah National Forest, photographed on the lands of the Eastern Cherokee. Photo by Rachel Veale.

Six months prior, my friend Alex and I came up with a crazy idea over dinner one fall evening: to attempt to beat the record on a 30-mile trail just southwest of Asheville, NC.

The Art Loeb Trail is a National Geographic recognized singletrack adventure that lies on Eastern Cherokee ancestral land in Western North Carolina. Starting in the flats of the eastern region of the Pisgah National Forest, the Art Loeb climbs over 4,000 ft through dense rhododendron tunnels, technical rocky Appalachian mountains and exposed balds in Shining Rock Wilderness before dropping several thousand feet to Daniel Boone Campground. From start to finish, the trail clocks in at 30.1 miles and about 9,000 feet of elevation gain.

A scenic view of Shining Rock Wilderness, photographed on the lands of the eastern Cherokee. Photo by Rachel Veale.

Alex and I share a love of trail running. A year prior, he convinced me and several other Outward Bound Instructors to run a 34-mile trail race in Virginia. After 2020 closed the door on in-person races for the foreseeable future, the attention of many runners shifted to setting Fastest Known Times (FKTs) on trails.

Created by a couple of trail runners about 20 years ago, the Fastest Known Time concept is a way to quantify and verify trail-running records. The women’s FKT for the Art Loeb stood at 7 hours and 2 minutes, and I decided I would train with the intention of beating it. “This will basically be my own personal 30-mile PCE,” I joked to Alex as we poured over a map of Pisgah National Forest on his living room floor.

The PCE, or Personal Challenge Event, is the traditional end to an Outward Bound course.

Often taking the form of a run, climb, paddle or other physical activity, the PCE is planned at the end of the course intentionally—to provide students with an opportunity to step into one final challenge after days, sometimes weeks, of physical and emotional demand on course. As Outward Bound Instructor Renee Igo explains, the PCE “gives students an opportunity to see how much physical and emotional strength they’ve gained, and be able to take that momentum forward in the transition back home.”

As I would later realize, the hours of running I was subscribing to in the months to come would push me to the edge of my limits, challenging my relationship with running—and pushing me to the edges of myself.

An Outward Bound crew preparing to face their own personal challenges on a rock wall. Photographed on lands of the Eastern Cherokee. Photo by Rachel Veale.

When one faces repeated stress, one can reach an intersection—with the choice to accept an invitation for growth, or deny it. As my training increased from running 40 to 50 to 60 miles every week over several weeks, I felt myself growing resentful toward the amount of space running was taking up in my life.

“I had arrived at an intersection. I could choose to continue forward and press onward, even amidst the discomfort and disconnection from an activity I loved—or I could choose to quit.”

Four weeks out from the set Art Loeb attempt date, and I was in a low mental place. “Why the %$&* am I doing this?” I seriously questioned myself as I put on my sneakers, still wet from a 22-mile trail run that morning, for a 10-mile run-turned-crawl on the local city greenway. I was so close to being done with my four-month training block, yet I felt disconnected from an activity that normally filled me with joy. That disconnection was terrifying—the love of running that I intimately felt when I made this goal months prior was absent, and without it, I felt lost. An activity that usually served as a container for stress relief was beginning to become a stressor.

And that is the realness of challenge.

Months ago, when I had set this goal in Alex’s living room, the idea of running 30 miles in the spring was an intangible dream on the distant horizon surrounded by the sunshine, cheering friends and celebratory post-run chocolate cake. As I settled into my training routine, in came the very tangible hard work of 6 AM alarms, solo hours on singletrack trails, bundling up to face the cold/wind/rain, facing my negative self-narrative and getting familiar with it and talking it down. As well as, stumbling through days on tired legs and a tired mind, and sacrificing important aspects of me to honor my training schedule.

And here I was, just weeks out from my anticipated personal PCE and feeling the strain of all of these training days: a build-up of months of physical and emotional stress. I had arrived at an intersection. I could choose to continue forward and press onward, even amidst the discomfort and disconnection from an activity I loved—or I could choose to quit.

A misty moment from one of Rachel’s many training runs. Captured on the lands of the eastern Cherokee / Black Balsam Knob. Photo by Rachel Veale.

In his appropriately named book, I Hate Running and You Can Too, Brendan Leonard speaks into the importance of connecting to challenge: “That’s the key here. To find meaning to the effort and make sure it’s worth it for you.” The next morning, I opened up my journal and wrote, “What parts of me am I honoring by continuing forward with this?” As I stared at the page, the words slowly came—determination, grit, perseverance.

I began reconnecting back to these core pieces of my character that had gotten lost amidst the stress of training. Even if my relationship with running had shifted, there were pieces of me that I could honor by continuing to show up. Here were lifeboats that would carry me through the rough waters of growth. Reclaiming this connection to my goal was essential in me continuing out the rest of my training. Finding meaning to the effort on my own terms pulled me back into a grounded mind space—and reconnected me to my challenge by my own choice. On Outward Bound courses, we believe that in order to access a space conducive to growth, students must determine for themselves if they want to participate.

Finding your own reason to face challenge ties you personally to the work it takes to get through it. Connecting to a challenge by your own choice reminds you of the active role you play in your life, enabling you to access the growth that lies on the other side of discomfort. To read more on this, check out the blog: Taking on Challenge in the Pursuit of Growth.

Flash forward to April 4th, 2021.

As I drive out to the trailhead at dawn, I remind myself that the majority of the hard work has been done. The hay is in the barn, and this day is a declaration of what I have to show for it. Similar to a PCE at the conclusion of a course, I realize that there is no distinguishment between journey and destination—they are one and the same. The training for a goal is where the growth is, and arrival to the goal is the cherry on top.

The day unfolds, and it is a celebration—of fitness, of community, and of the end of a long road of hard work. I am supported by dear friends near and far, and I run hard. 30.1 miles and 7 hours and 39 minutes later, I arrive at the finish line. I did not break the record—but I broke through parts of myself, and came out of a four-month experience with a deeper understanding of who I am and what my body and mind can handle.

A month has passed since my Art Loeb effort.

Spring has sunk its roots into Western North Carolina, and the shifting of seasons has awakened parts within me that have lain dormant for months. Old pieces of myself that were tucked away amidst the cobwebs have dusted themselves off and rerisen to the forefront of my consciousness.

I am remembering what it feels like to awaken to birdsong and soft sunlight at dawn—I am remembering the way spring’s gentle entrance colors my perspective with a soft joy that was lost amidst the damp chill of winter. I am remembering, too, pieces of my relationship with running that have returned to accompany me on solo trail runs in a forest awakening with life.

It is a relief, this remembering—and a reminder that nothing is permanent. I can only acknowledge and celebrate the present phase I am in, and treasure all the highs and all the lows of an experience, knowing that they are attached to the same thread–being alive.

Author Rachel and her friend Alex after their 30.1 mile run on the Art Loeb Trail.

About the Author

Rachel Veale is an Instructor for the North Carolina Outward Bound School. With a degree in Electronic Media and Communication from Texas Tech University, Rachel thrives at the intersection of content creation and outdoor spaces. Her go-to road trip snack is black coffee and donut holes. When she isn’t on course, you can find her running down a trail in western NC or chasing golden hour with a camera in hand.