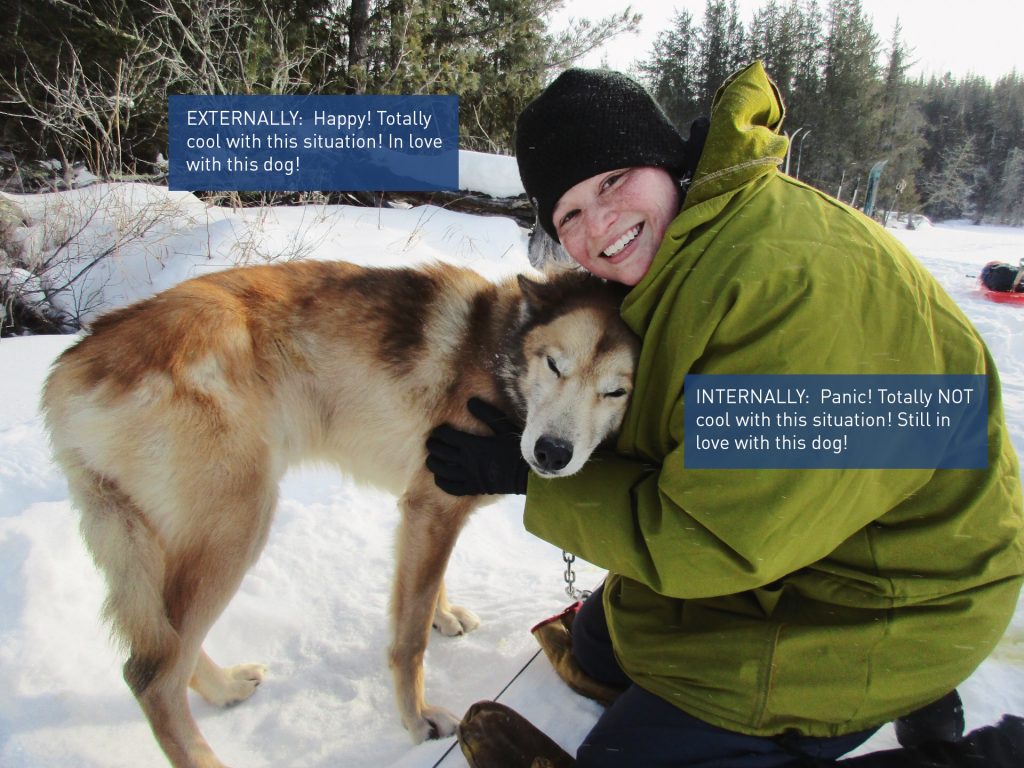

I’m the “type” of person people expect to go on an Outward Bound expedition, and not only because I work for Outward Bound. Most of my friends use words like adventurous, bold and daring to describe me. (I checked.) I’ve had some extremely fortunate opportunities to do crazy things, like bungee jumping and swimming with whale sharks, and I’ve seized them all. On the outside, I have a pretty exciting life. I’m put-together. I’m confident. AND I have the most beautiful dog in the world. (I checked.)

But I’m going to share with you something I’ve never shared with anyone.

Are you ready? Ok. Here goes.

On the inside, I’m often a wreck, because I don’t know how to deal with my emotions.

The minute I have an uncomfortable emotion, I take it into my hand, roll it up in a little ball, like a child does with Playdough, and stuff it down into the pits of my soul, never to be seen again.

Sadness? Going in the soul pit. Embarrassment? Soul pit. Inadequacy? Put it in the pit! Vulnerability? Very, very bottom of the pit.

You get the idea. Shockingly to me, this is not a sustainable way to live.

I was immediately on-guard when one of the first things my Boundary Waters dog sledding Instructors said to us was “be vulnerable and keep us in the loop on how you’re feeling and where you’re at.”

Umm, ew.

But I’ve always been a good student, so I followed instructions and began by confessing to one of my Instructors on day three that I was having an anxiety attack. Most of my family doesn’t even know I have an anxiety disorder, and here I was telling a stranger. I hated it. So I put that feeling of vulnerability in the pit and tried to forget about it! Bye!

This happened a lot in the first few days of the expedition. The whole course was a tsunami of uncomfortable feelings. Going 10 miles on your first day ever of cross country skiing is uncomfortable. Pushing a several hundred-pound dog sled up a hill and sleeping on frozen lakes is uncomfortable. Pooping in subzero temperatures is very uncomfortable. Snot freezing the moment it enters your nostrils and wearing the same clothes for 10 days is uncomfortable. Post-holing* with every step is uncomfortable. Getting sawdust in your undies from sawing the tree you just felled is very uncomfortable.

Photo courtesy of Shelby Jumper

The pit of emotions was filling up nicely. And then came day four, my hardest day.

That day felt a minimum of 75 hours long. The wind was strong, and the snow was deep. I don’t know how much you know about dog sledding, but it’s not Balto. It is hard. You don’t ride along while the dogs do the work. You grunt and run and push and pull alongside the dogs. It’s a team effort. And you know what a few hundred pounds of sled does in waist-deep snow? It sinks. That’s when it feels impossible.

The mushers and skiers were sinking and getting stuck the whole day. It took the dog teams and all eight human members of the crew to get the sleds through portages. We even had to get the sleds up a cliff, which is, in fact, as hard as it sounds. We later learned that we went an average of one mile an hour that day. I don’t even know if you can walk that slow. In a word, it was grueling.

Photo courtesy of Shelby Jumper

I’ve never felt more inadequate in my whole life. I’ve been an independent person from a young age. I don’t need help with much, and you better believe I will be near death before I ask for it. It’s a matter of pride. I’m not always the best at something, but I’ve never been The Worst. And I felt like I was The Worstest Worst at this. It felt like everyone was catching on faster and having an easier time than I was. I not only felt like a burden (my least favorite feeling), but I HAD TO ASK FOR HELP. It was a like a quadruple whammy of uncomfortable feelings.

Shove. It. In. The. Pit.

When we finally got to camp, we still had several hours of camp setup that included but was not limited to: caring for the dogs, setting up shelters, collecting dead and down wood, cutting down a tree, sawing and chopping that tree, chopping a two-feet deep ice hole for water, building a fire and cooking dinner. We finally sat down to eat around 11 p.m.

We all slept like rocks that night, and I woke up feeling hopeful that the hardest part of the expedition was behind me.

Day five was to be the start of our 24-hour Solo period, and surprisingly, I wasn’t too nervous about it. I felt like our Instructors had prepared us and we knew what to expect.

Knowing how totally beat we all were from the day before, our Instructors presented us with two options for the remaining five days of the expedition. Option 1 was an 18 mile, trail-broken path, that would be challenging, but not quite so backbreaking. Or there was Option 2, a gnarly 26 miles of mostly unbroken trail and unknown conditions that was guaranteed to be brutal, but doable. The Instructors left it up to the students to discuss and vote for a route. There was no way any of the perfectly sane people in my crew would vote for Option 2 after living through the day before. No way. But this is how the discussion went:

“I say let’s do the gnarly one.”

“Yeah, I agree.”

“We’re out here. Let’s just do it.”

*stunned expression of disbelief*

There was no way this was happening! This was supposed to be an obvious choice. I realize I’m about to do what I hate doing most in the universe. I’m going to be vulnerable. I say, “Uh, guys. I just want to let you know that whatever we decide, I’m going to give you 110%, but I honestly don’t know if I am physically able do Option 2. I don’t want you to feel like you have to pick up my slack.”

My incredible crew gave me their attention, listened and understood my point of view. But they disagreed with me. They thought I could do it. When the Instructors came back, we took a vote. Everyone raised their hand for Option 2 but me.

I could feel the tears welling up as we stood there, still in a circle. I kept my head down as a few fell and immediately froze on my anorak. Frozen Tears on My Anorak is a country song I’ll be waiting on forever.

I kept it together while we went over a few final things before embarking on Solo. I could feel the emotion shifting as it churned its way into anger. I wasn’t mad at my crew. They’re compassionate, positive, encouraging, courageous, stellar human beings and some of my favorite people ever. I was mad at myself. Why was I not better at this? Why was I not stronger? An Instructor reads a beautiful quote from a very wise person, but I’m mad and can only think of how dumb it sounds. We set off for Solo in silence, which also felt dumb.

Photo courtesy of Shelby Jumper

I trudged my way through the snow to my Solo location and immediately got to work, still mad. I set up my shelter and set out in search of firewood. I started aggressively collecting dead wood, snapping each stick as if it was one of the many weaknesses I felt so keenly aware of. The more I snapped, the madder I got. I dragged my small collections to the shore and dramatically threw them into the growing pile. There was no one around to watch this unfolding drama, but it felt good to let the universe know I was mad anyway.

I was mad I couldn’t carry more wood. I was mad my pile wasn’t bigger. I was mad I was in knee-deep snow. I was mad I didn’t have the self-confidence to vote with the rest of the crew. I was mad I was not curled up on the couch with my dog and a cup of tea, watching a BBC nature documentary.

I sank into the snow, took a huge gasp and ugly cried right there in the woods. I’m not talking about a couple of tears. I’m talking about full-on, shoulders-heaving, snot-running, overbite-showing, ugly crying. Every uncomfortable emotion I had shoved in the pit came spilling out. I was truly overwhelmed.

As I sat there, dripping snot and tears into the snow and feeling sorry for myself, I realized that all the uncomfortable emotions shoved in the pit were just and only that: uncomfortable. Not life-threatening, not shameful, not embarrassing—simply uncomfortable. By shoving them into the pit, I gave them power—power to fester and grow, and the power to control me, instead of the other way around.

And just as quickly as the tears came, so did the laughter. I was a real mess, stinky and sweaty with frozen snot on my clothes, but I had finally gotten it. I couldn’t push discomfort away. I had to welcome it. Sit with it. Validate it. And then keep it in check. I’m not my emotions, and certainly not the negative ones. Just because I have feelings of inadequacy and weakness doesn’t mean I am those things. It’s moments of doubt that will pass, just like everything else.

“There is more in us than we know.” (Kurt Hahn)

I had spent a year working for Outward Bound, slapping that quote all over the website, posters, ads and brochures. But I never got it—not really—until that moment in the snow. Kurt was right. There is so much more, and thanks to the expedition, I caught a glimpse of it.

I got myself together, finished gathering up wood and had a wonderful Solo, on which I slept 12 hours.

The rest of the course was hard. It was uncomfortable. But it was incredible. It was worth it. And I did it! I spent 10 whole days on a dog sledding expedition! How amazing is that?

It’s been seven months since the course and I still think about it every single day. I could write a hundred essays about it—how superb sled dogs are, how much love I have for my crew, how someone pulled out cookie dough on day eight and I actually cried.

Instead, I’ll leave you with this: I’m different now. Everything is a little different now. The pit is gone—it is full to the brim with joy, compassion, optimism, confidence and trust. I meet challenges and uncomfortable situations head on because I’ve seen what’s inside—I’ve got this. I’m surer of myself and my abilities, I trust people easier (thanks to my crew, The Golden Circle), and I’m not afraid to fail.

This expedition was one of the most profound learning experiences of my life. I’m still learning from it; I probably always will.

Photo courtesy of Shelby Jumper

*Post-holing: stepping through snow calf-to-knee deep.

About the Author

Shelby Jumper is the Web Content Administrator for Outward Bound. Her hunger for adventure has taken her all over the world—from hiking in the Swiss Alps to exploring the South African Wild Coast to swimming with wild whale sharks in the Philippines. She’s passionate about getting people outside, the medicinal value of laughter and her dog, Scout. She writes from Golden, Colorado.