Feedback is a practice that is both rigid and creative. It requires methodical thinking and sophisticated emotional intelligence. And in order to understand how to give and receive feedback at its best, not only do we need guidelines, but we need to root ourselves in emotions. This article is about the convergence of the two sides of feedback: the rigid and the fluid. How do we maintain objective feedback while also acknowledging others’ emotions? How do we support others emotionally while still giving them feedback that serves their growth?

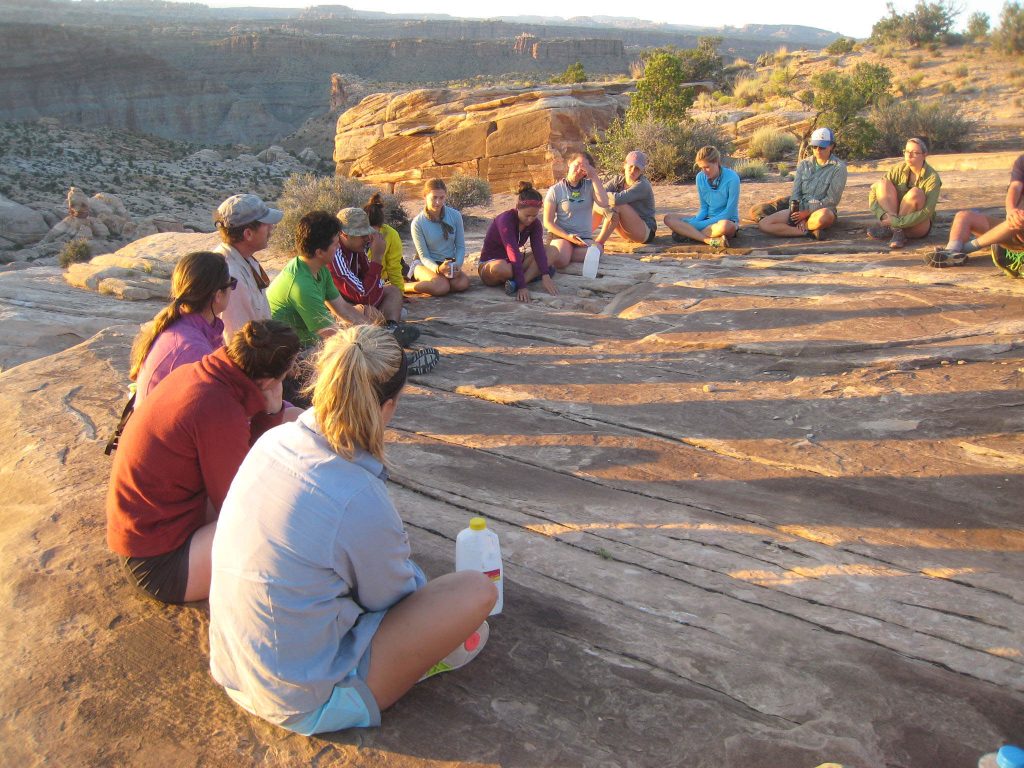

Photo by Kim Reynolds.

Balancing Act

Sometimes, instead of walking the line between compassion and structure when giving feedback, I fall to one side, making my feedback lopsided. It is, to me, a vivid display of my own tendencies to be vague and nice. And understanding that this is my tendency has helped me to be more aware of myself as I give and receive feedback. When considering your own experiences giving and receiving it, what tendencies have you noticed in yourself? Are you honest? Nice? Unemotional? Direct? How has this influenced your experiences giving feedback? And how has it influenced your experiences receiving feedback?

Why Give Feedback?

In order to better understand what makes feedback work, we need to understand why we give and receive it. At Outward Bound, we often discuss the four states of competence. With any given skill, we each have a certain level of competence. My competence at playing tennis is low. My competence at tying knots is high. My competence at baking a blueberry pie is somewhere in the middle. Consider competence as the “x” axis of a graph. It is a spectrum, and depending on the skill, you may lie at any point on this spectrum.

The “y” axis is self-awareness. I am aware of some things about myself and unaware of others. For example, I am aware that I like to drink coffee, and that I am not excellent at painting my nails. I was previously unaware that I get distracted during conversations about politics, and that I am very encouraging of my colleagues. There is also a whole undercurrent of information about myself that I am still fully unaware of. These are things that go unnoticed by me, but other people may see regularly. Just like competence, self-awareness is a spectrum, and I can be anywhere on the spectrum, depending on the skill we are talking about.

If we consider the relationship between competence and self-awareness, we then have four categories of possible competency.

Conscious Competence: Something I know I am good at

Conscious Incompetence: Something I know I need improvement at

Unconscious Competence: Something I do not know that I am good at

Unconscious Incompetence: Something I do not know that I need improvement at

I often hear that the goal of feedback is to move some of your unconscious competence and unconscious incompetence into the conscious zone. However feedback can also shine light on our conscious competencies, or give specific advice regarding conscious incompetencies. What is important is that you know the goal of the feedback you are giving or receiving. Is it intended to encourage yourself or others? Or is it intended to help you or others see something that has been otherwise overlooked? There are many possible goals, and it can be useful to think carefully about the purpose before you dive deep into the feedback.

Above All, Compassion

Every organization I have worked for has its own guidelines on how to give and receive feedback. However, year after year, course after course, my mind is always drawn back to the rule of compassion. It’s simple: feedback is about compassion. As you read the following rules, try adding this statement to the end of each sentence to see how the meaning shifts: “and above all, be compassionate.”

- Feedback should be given like a sandwich: two positives wrapped around a delicious constructive.

- Feedback should always be phrased consistently: “It was effective when…”, “It could be more effective if…”

- Constructive feedback should be specific, concise and actionable.

- Feedback should not include compliments, or comments on the person, but instead focus on observations about their behavior.

- When receiving feedback, you should not speak unless to ask a clarifying question.

- Never give feedback at Disneyland or during a thunderstorm, or before a burrito dinner, or in the middle of asking somebody to marry you (this is impolite).

I find these rules to be incredibly helpful and especially when I add the rule of compassion. After reflecting on feedback given to her by a colleague, one of my favorite supervisors expressed compassion like this: “…it’s important to let people have their feelings and be an ear for them without having them figure out how to solve the problem right away.”

Rooting ourselves in the relationship reminds us that we are giving or receiving feedback because we care. Whether the feedback you are engaging with is positive, constructive, hard, easy, happy or even frustrated, the relationship between you and your feedback partner is the backbone. Treating your partner with care and treating yourself with care brings an authenticity to the feedback that can’t be replicated in any other way.

Feedback and Ourselves

Throughout my time at Outward Bound, I have had different relationships with feedback. At times I have respected and appreciated it. I have also felt disconnected from it or resented it. I have broken up with it and moved out of our shared apartment. It has been a process. Whatever your relationship is with it at the moment, consider it as something that changes and grows. Sometimes feedback allows us to see aspects of ourselves in a new light, while other times it helps us to keep engaged in a process we find challenging. Sometimes feedback shows us our gaps while other times it shines a light on our assets. But what remains constant, no matter the specific goal, is that feedback is about caring: caring for ourselves, caring for our people and caring for our collective growth.

About the Author

Rebecca Fenn is an outdoor educator, originally from California, who instructs for NYC Outward Bound Schools and North Carolina Outward Bound School. After graduating from University of Chicago with a major in Human Development, Rebecca worked in college admissions and then began her journey toward outdoor education. She became the Life After Eagle Rock Fellow at Eagle Rock School and Professional Development Center, a wilderness-based boarding school in Estes Park, Colorado. There she taught at-risk students “Math for Life” and served as both a college counselor and as a vocational counselor to prepare them for life after Eagle Rock. Upon receiving a Master’s Degree in Education Policy from Harvard, she decided to delve deeper into the Expeditionary Learning model by taking on the challenge of becoming a Field Instructor for Outward Bound. Rebecca is a cartoonist, artist and writer, and loves the challenges and rewards of working with youth in the outdoors. She is always interested in learning more about educational systems, cultures and practices in the United States.

OTHER POSTS YOU MAY LIKE

Read More

Read More

Read More