Many of us find ourselves stepping into the role of teacher these days. While the end goals of our instruction may differ, I think we share a common process—hoping that we can build our students into more confident, independent learners through our instruction methods. Outward Bound Instructors teach a wide range of skills from navigating the backcountry to sewing a rip in your pants. Through it all, we employ several strategies to empower our students to take ownership of their learning, their expeditions and their lives.

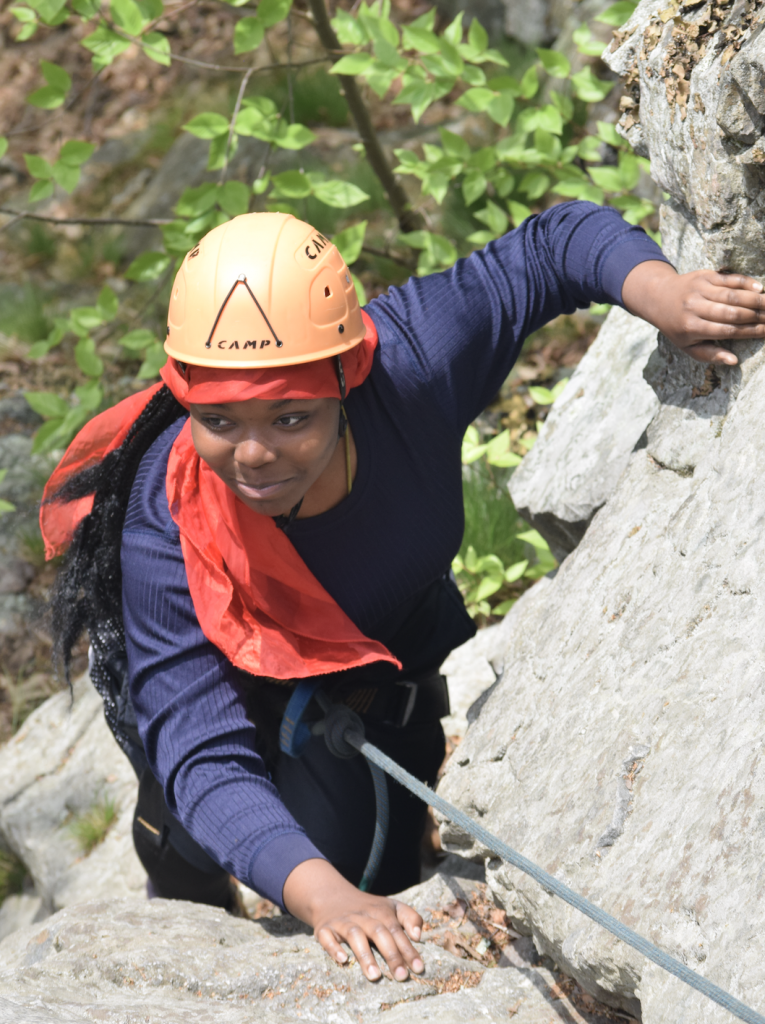

Photo by Ellsworth Faris

Perfection Isn’t Expected

One of our goals is for our students to discover the power that mastery confers. Craftsmanship is a value held highly by Outward Bound, and we seek to give students the opportunity to experience the satisfaction of a job well done. We’re not there to punish mistakes or to allow nature to punish our students’ best efforts. Perfection isn’t expected; we commit to strive for excellence, recognizing it will never be achieved. Striving is ongoing.

Outward Bound courses employ natural consequences, like when rain soaks the gear left out of the tarp overnight. This happens only after students have had a chance to master the needed skills. Instructors help students practice new skills repeatedly before allowing a natural consequence to occur, rather than teaching it once and expecting mastery. Especially for teens pushing away from adult experience and authority, the natural consequence will be a much more effective and memorable teacher. However, not all natural consequences can be managed by the careful eye of an Instructor. Constant rain for the first week of an expedition, for example, is a harsh and unforgiving teacher out of our control. Rain will soak through everything eventually, and Instructors and students alike live in the same world and make the best of it, which becomes its own lesson.

Students Become the Experts

Another method we use to build up our students is teaching in a progression, starting out with simple skills and building in complexity as we revisit topics. Map reading is an example of a complex skill that’s new to many students. There’s no exam to study for—every day is an opportunity to practice skills, but it’s also important for the expedition to feel fun.

When I’m instructing, I often teach a beginning map-reading lesson where students identify major features on the map and learn how to match real-world features with map features. I teach them how to orient the map as we travel, and then check in with students throughout the day to see where they think we are on the map. I point out major landmarks as I see them in the real world and ask students to find them on their maps. After several days, as each student has had the chance to become more familiar with the maps, I may either reteach the original lesson or add in additional map features, like topographical lines or clues in reading the land for where a trail might go. Later in the expedition, we may encounter a large lake where a compass bearing could be useful. Compasses become another tool for students to add to their navigation toolbox.

Photo by Jason Estrada

Teaching skills in a progression like this allows for a review at the start of each lesson but keeps lessons from getting long-winded and overwhelming. Teaching a skill in parts over the span of a week or more allows me to get to know my students and their interests and learning styles better. As some students gain proficiency, I can prompt them to assist their peers, increasing the team’s autonomy and giving students a chance to become the experts.

Training, Main and Final Phases

On a broader scale than a skills progression, many courses have a core structure of a training phase, a main phase and a final phase. Courses often begin with a training phase, in which the Instructors teach and role model new skills and are present when questions come up. The amount of new material students may have to learn can be extensive, from organizing their backpack to paddling skills, to how to chop an onion to communication skills.

On the main phase of a course, Instructors step back to allow students more autonomy. Instructors give students the chance to practice their skills before Instructors step back in to coach or facilitate. Students set goals for what they would like their biggest takeaways to be. Instructors help students build habits to be successful on the expedition, but also allow the group to take shape and make more of its own decisions.

During the final phase of the expedition, Instructors step back further to allow for as much independence and autonomy as possible. Students take ownership over what each day feels like. Because the course isn’t for the benefit of the Instructors, but for the students, it’s important for Instructors to remove their ideas and priorities and allow for students’ priorities to shine through as much as possible. The idea of the final phase should sound intimidating to new students, who lack the skills to be ready for that level of independence. Each phase looks different and lasts a different length of time given the student group. Instructors work to match the responsibilities handed over to the abilities of the students, so that challenges feel difficult but not impossible. Failure is recognized as an important learning opportunity but isn’t meant to be the overarching feeling of the course. Instructors always remain in a position to intervene when new hazards are encountered, or when conditions exceed student abilities. Safety always comes first, and due to the unpredictable nature of traveling in the wilderness, Instructors are always prepared to step back into the spotlight to manage risk.

Teaching Is a Learning Process

Through managed use of natural consequences, teaching complex skills in parts, and building students toward independence, we seek to make learning a positive, inspiring process—even if students’ attempts aren’t always successful.

No matter where your classroom is today, you can ask yourself whether your students are in the training phase, the main phase or the final phase of their learning. You can ask yourself how to break a lesson into smaller pieces, or what you can teach today that builds on something they already know. Teaching itself is a learning process, and it’s just as important that we recognize and celebrate our accomplishments as we strive toward excellence.

Teaching is one way we build an atmosphere for resilient learners and leaders on an expedition. This is transferrable to all types of classrooms—whether that’s in a school, through a video call at home, or in the middle of the wilderness.

Photo by Ethan Goldstein

About the Author

Renee Igo was an Outward Bound student at age 15, and has been instructing wilderness expeditions for the Voyageur Outward Bound School for the past eight years. When not instructing, she holds a variety of other teaching positions and raises sheep in Maine.