Gap Year: The Option for Me

I didn’t know college was optional until I was well into high school. Through a combination of a very sheltered childhood and high academic expectations, my understanding of the world proceeded accordingly: first comes kindergarten, then elementary school and middle school, followed by high school and, ultimately, college. Everything you did up until college determined which college you went to and therefore your potential for success for the rest of your life. Casual. No pressure.

And I don’t believe my parents tried all that hard to set the record straight: I was a decent student but willful, impulsive and desperately grasping at independence. However, as a teenager I began to seriously examine my culture surrounding accomplishment and higher education. I recognized college first as optional, then as a privilege. I discovered my mom had graduated high school early and scooted off to France to pick grapes in a vineyard for six months. (I didn’t know the name of the curly-haired young French guy in the black-and-white photo, but I sure as heck recognized the glow on my mom’s face.) With some prodding, I learned that neither of my incredibly successful parents had finished college in the traditionally allotted four years. By the time I was a senior in high school, I still wanted to go to college but I had identified the wiggle room in my future trajectory.

I had also started to crack under the pressure.

I cracked under the pressure to get straight A’s in as many honors and AP classes as possible. I cracked under the pressure to have meaningful summer experiences to write college entrance essays about. I cracked under the pressure to serve my community, be a good friend/daughter/sister, make some money and be thin and attractive. I cracked trying to be the best at all of my many extracurricular activities so I could show colleges I was both well-rounded and exceptional. I cracked trying to balance all that while simultaneously experimenting with all the world had to offer, while trying to discover who I was and who I wanted to be. Plus, hormones.

Ella is shown at her high school graduation.

It all culminated my senior year with the willful and impulsive decision to take a year off from school before going to college. There were whispers. Ten years ago the concept of a “gap year” was only starting to take hold in the U.S. Many of my friends and their parents thought I had gone off the deep end, that they were witnessing my swan dive into a life of wasted potential. But I was wiped; I was over it and could not imagine moving into an even more academically rigorous stage of life. My parents convinced me to apply to schools and defer, for which, in retrospect, I am incredibly grateful. This allowed me to go wander off that year without worrying about applications and gave me a solid place to land after what turned into one doozy of an experience.

Failure is Not an Ending, But a Beginning

My first stop was Florence, Italy. I spent two months studying Italian at a small language school and living in an apartment with two Swedish girls. Then I travelled. I visited Istanbul and embarked on a whirlwind tour of Europe: nine countries in four weeks with a train pass and a backpack. Mostly I ate, got lost and visited art museums. I travelled alone but would meet new people and old friends in each place. I learned to appreciate the bitterness of coffee and how to push through the loneliness that encroached every evening around sunset. Being sick away from home is awful, but I learned how to take care of myself. I also figured out pretty quickly that I couldn’t play by the childhood rules of “stranger danger” if I was going to make new friends, so I grew bolder while I honed my instincts about people.

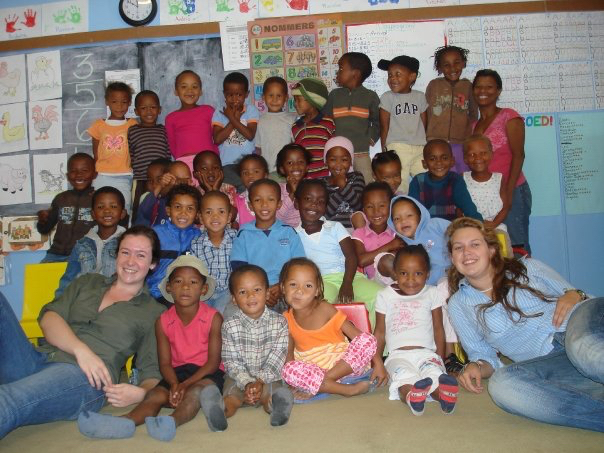

Then, after a few months of scooping ice cream back in Maryland, I left for South Africa. For three months I lived and volunteered in the countryside just east of Plettenberg Bay in South Africa. I worked in a pre-school and was responsible for a class of forty 3-, 4- and 5-year-olds. Not to put too fine a point on it, I got my butt kicked. As a high-achieving teenager from an affluent neighborhood I had in my mind that I would come to Africa and “do good.” I admit with chagrin that I thought of it as “balancing my karma” after my self-indulgent trapes around Europe.

None of that happened. I had no idea what I was doing; I didn’t speak any of the languages and I had never worked in a classroom before. Most importantly, I didn’t know what questions to ask, let alone that I needed to ask them. I did my best but, given the circumstances, my best was dismal. My ignorance and arrogance were made abundantly clear. For many years after I felt that I had “failed” in South Africa. I was so used to being graded, to achieving at a high level, to having strict parameters for success, that “failing” was the only way I could understand the experience. And I had never failed before.

Ella is shown with her class in Kurland Township, South Africa.

It’s been ten years since I returned from South Africa; ten years since I went back to work at a Ben & Jerry’s in an affluent D.C. suburb; ten years since a customer complained to corporate about my poor attitude in the face of their sprinkle-related concerns. South Africa had a profound and immediate effect on how I viewed the world and my place in it, and that was not comfortable. But nothing spurs growth like discomfort. It took many years for me to move from embarrassment over my South African “failure” to gratitude for the experience. Because I did fail! I failed in my goal to “do good,” to profoundly and positively affect the lives of my students. Instead, those students taught me more than any professor or any class; they taught me the depths and complexity of the world’s ills, the futile effort needed to combat those ills, and the absolute necessity of the effort, regardless. They taught me humility, that I am a forever student, that failure is not an ending but a beginning.

Photo by Justin Brewster

Embracing Failure & Achieving Success

Five years after graduating high school I graduated summa cum laude from Indiana University with degrees in Arabic and Religious Studies. Getting my “Woo! No Parents” ya-yas out before college allowed me to focus on academics in a way I never had before. Also, my experience in South Africa taught me that immersion into a new culture and new community takes time and commitment; because of that, when I decided to study abroad in Jordan, I did so for a year instead of the customary semester. That in turn allowed me to travel extensively around the Middle East and gain a proficiency in Arabic I would not have otherwise.

To parents out there: I recognize that there is a balance when structuring a gap year. When I graduated high school, every hour of my life for the last 18 years had been planned, programmed and accounted for. If I had embarked on my gap year entirely untethered, I would have floundered and my mother would not have slept. Programs like language schools, Americorps, and Outward Bound can work as stepping stones to complete independence, depending on what interests your recent graduate.

I have worked for the Colorado Outward Bound School for four years now. More and more I hear my students talking about taking a gap year before or during college, and I am grateful they know it’s an option. Many of these students take an Outward Bound Gap Year/Semester or an Instructor Development Course. An example of an Instructor course includes 50 days of rock climbing, mountaineering, wilderness medicine, and perhaps a final expedition in another region of the country or abroad, all during which students learn the nuances of backcountry living and outdoor education. But really, it is so much more.

Ella is shown instructing a 22-Day Alpine Backpacking course in the North San Juan mountains. Photo taken by Grayson Kemp.

Room to Fail & Room to Grow

Ethan O., a student on an Instructor Development Course this summer, took time off from college when a combination of breaking his clavicle and wanting to change his major would have put him significantly behind. Ethan was drawn to the structure of the course and the college credit he could gain, and said it felt like “a new leg in a journey” rather than a time filler. In learning how to climb, he combined his natural ability with the drive inspired by this new passion, noting that “For the first time in my life I really planned ahead.”

Justin J., who instructed the Instructor Development Course this summer, had been in his students’ position five years prior. He pointed out that, while his Instructors taught him how to survive in the mountains, that was only the barest beginnings of all he learned on his course. He is intimately aware of all that his students can gain from their Outward Bound course, and that influences the way he teaches it. He knows where the priorities lie:

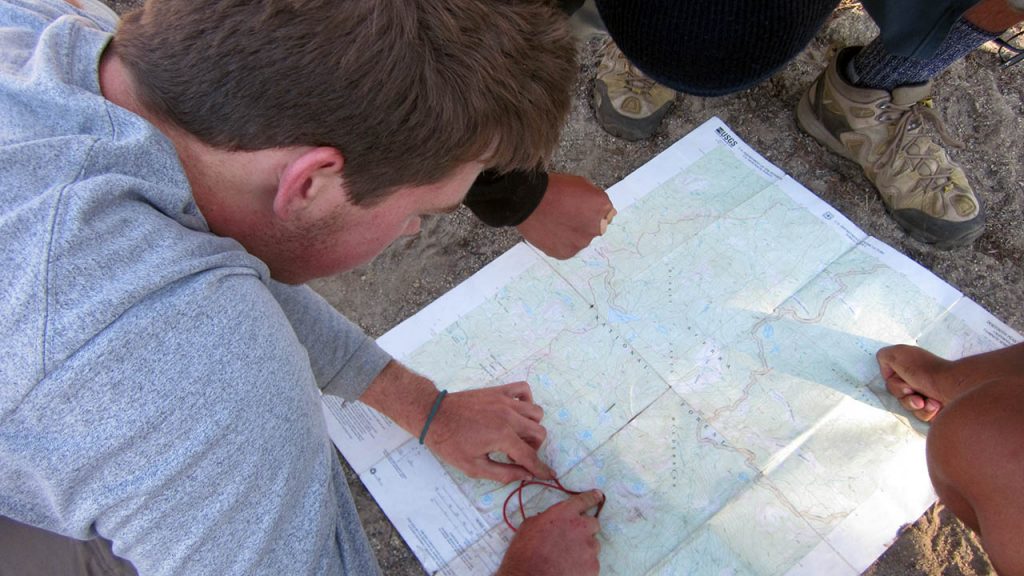

“That 50-day Outward Bound course taught me more about myself than 18-odd years of schooling ever did. I learned how to set up tarps in the wind and how to tie a truckers hitch and how to light a whisper light stove and how to read a topographical map and use a compass…I also learned how unnecessary it is to apologize every time I said or did anything. I learned the difference between “compassionate acts” and “true compassion.” I learned…that I can make people laugh which gives me joy. I learned that when I am presented with a challenge I can use whatever tools I have at my disposal to overcome said challenge, and if I don’t have any tools, I can just make them up and figure it out…I not only learned how to do a lot of really neat stuff, but I also learned extremely valuable lessons about myself and the world around me, perhaps the most important lesson of all being that I finally learned how to love myself.”

Photo by Rikki Dunn

It has become ever clearer to me working as an outdoor educator that our school system, while useful in many ways, on its own does not effectively prepare students for the rough-and-tumble realities of life. As Chris K., another Outward Bound student this summer put it, in academics, “You just kind of followed your interests. You never really followed your heart.” At Outward Bound we hold the boundaries necessary to protect students from harm, but not from themselves. As you would hope from any gap year, our students have room to fail and through that room to grow. We know, from our own experiences and those of our students, that tenacity, resilience, self-determination and self-confidence all spring from the rocky soils of failure, hardship and uncertainty. We know it’s never easy when you follow your heart.

Photo by Mareya Becker

***

Interested in learning more about gap years? Talk with one of our Gap Year/Semester specialists.

About the Author

Ella Hartley has worked for the Colorado Outward Bound School (COBS) since 2014 as an Intern, Logistics Coordinator, Instructor and General Minion. Leadville, Colorado is homebase for a life spent playing in the surrounding Rockies, traveling and hiking obnoxiously long trails. Case in point: last winter Ella hiked the length of New Zealand in order to raise money for the COBS Gruffie Scholarship Fund for young women… and because 1,800 miles of beaches, mountains, farms and mud sounded like fun.