In Jack London’s 1908 classic short story, To Build A Fire, the author tells the gripping tale of a hardy but slightly overconfident man traveling on foot in winter in the Yukon, with a dog as his companion. Not only was it winter, but in brutal cold of -75 degrees Farenheit. As the story progresses, the man stops to build a fire more than once to keep himself from freezing. The story does not end well (for the man), but I’ll leave the details of what happens for you to explore.

To Build a Fire underscores the importance of knowing how to build a fire in the wilderness. While it may not be essential for day-to-day travel, if you get wet or cold, or both, a fire can be a lifesaver.

A campfire is also one of the greatest delights when living in the out-of-doors. Friends gathered around the campfire in the evening means camaraderie, warmth and a great way to end the day.

Important conversations happen around on a campfire on an Outward Bound course. The crew pictured here is reflecting on the day’s activites. Photo by Ryan Harris.

When is it okay to build a campfire?

First, be sure to do your research on the campfire rules and restrictions of the area you’ll be visiting. For example, each national park has its own rules on where and when you can have a campfire. Special restrictions may be in effect, such as a campfire ban if it has been windy or dry. When it’s very windy AND dry, fire can spread like, well, wildfire. Hundreds of thousands of acres of public lands, like forest service and park service lands, have been destroyed by overconfident campers who built fires when they shouldn’t have. According to this source, “…about 60% of fires in national parks are caused by humans,” because of campfires, smoking, fireworks and other causes. So be aware of where your surroundings, including any fire bans in effect for the area you’re camping in, as they are put in place for good reason. And make sure it’s not very windy.

Another major factor to consider: is there wood available? Is wood in short supply? If you are in a really dry environment where trees grow very slowly, there may not be wood available without damaging the trees, which you will do if you take wood from standing trees. If there’s not a lot of wood available, it may not be healthy for the environment to have a fire, so use a lantern, flashlight or other light sources. Many parks don’t allow visitors to collect downed wood, even if it’s close to your campsite. Be sure to check before bringing firewood with you, as some national and state parks don’t allow it to be brought in because “people can unknowingly bring pests and disease into the parks on their firewood.” In this case, firewood is likely available for a small fee.

What type of wood should I use?

Only use wood that’s down on the ground. This wood will be dead, not green, and easier to burn.

Organize your wood as you collect it:

- A pile of tiny, dry pieces the size of a match stick or smaller. These will be the fire starter.

- Make a second pile of sticks that are the size of a pencil or smaller.

- Then a thumb-sized pile, and finally…

- Sticks larger than that

Where should I build my campfire?

If there’s an established fire ring, as there are in national parks like Voyageur and Joshua Tree, you should use that and not disturb a new area. Look for established fire rings in other areas that are popular for camping.

When looking to build a campfire, be sure to look for established fire rings you can use.

If possible, build your fire where you have access to water. You’ll need it to be sure the fire is out cold, and you don’t want to use precious drinking water if you aren’t near a water source.

If there’s no established campfire ring, how can I build a fire without damaging the environment?

Here’s where Leave No Trace™ (LNT) comes in. As more people get out and enjoy the wilderness, it’s important that we all minimize our impact. When you build a fire, think about ways you can leave the site looking natural when you depart.

If there is no existing fire ring, you have a chance to practice the LNT philosophy. There are several methods for doing this. You can dig a circle the size of your fire (about two feet), scoop out the top soil, which is alive with microorganisms, and set it aside on top of a ground cloth.

Or you can build a mound fire, where you gather mineral soil (sand, or soil from an uprooted tree) and place that on top of a ground cloth, about four inches deep. Build your fire on top of this dirt. The mound will protect the living top soil, and the plastic helps make cleanup of the fire site easy. Since heat rises, your plastic sheet will be insulated by the four inches of soil.

Keep water handy in case a spark or a small coal leaves the fire area, and so that you can put the fire out before turning in for the night.

What if I’m having a hard time getting it going?

The key here is AIR.

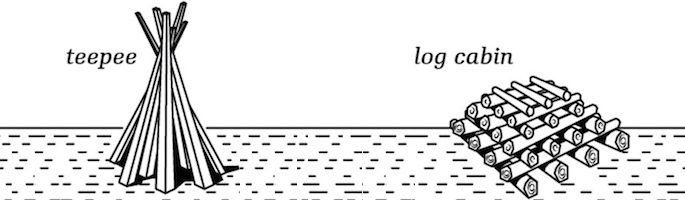

Campfire Setup: Teepee versus Log Cabin

When you build your fire, create a structure where there’s enough air to allow circulation below and around the wood. A “teepee” or “log cabin” structure does just that. In a teepee, you can put medium sized (thumb-sized) pieces of wood at an almost vertical angle, with tops touching for support. Then put smaller (matchstick sized) twigs inside the teepee. This structure gets flame under the larger wood and allows for air flow.

The log cabin shape also does this well. Put two sticks (thumb-sized or larger) parallel to each other on the ground. Then put two sticks of similar size perpendicular to those, and on top of them, starting a mini log cabin shape. Put fire starter (matchstick sized twigs or shavings) inside the cabin formation, and add small sticks (pencil size) to the fire as it grows to burn the outer sticks. This allows for plenty of air flow.

And then, blow on it. Lots! It helps to have two people. One person can be the bellows, while another “feeds the flames” with the right-sized sticks.

How big of a fire is okay in the wilderness?

Big bonfires create several problems: they use far more wood, and also increase the chances that the fire will reach branches overhead if you are in dense forest. Big fires use big wood, and you’ll likely end up with big, charred chunks, which are unsightly for future campers and do not comply with Leave No Trace ethics.

So, keep your campfire small, about two feet across. It will be easier to put out, maintain, and will be gentler on the land.

How should I put out the fire?

Before you leave the fire to slide into your sleeping bag, be sure it’s out cold. That means that you can put a hand on anything in the fire area and not feel any heat. This usually requires water.

Pour water over any remaining hot coals, and stir it into the ashes until all the embers are cold.

Leaving embers to burn out on their own risks an opportunity for a forest fire to begin. Wind can pick up and blow sparks and embers, lighting dry leaves and twigs into flames. Don’t take any chances, and put your fire out cold.

You may sing around your campfire, dry your socks, or burn wood to keep warm as Jack London’s character did in To Build A Fire. As long as you master a few tricks, and practice Leave No Trace, our ancient friend, Fire, will leave you with sweet memories of your time in the backcountry.

When you master all things campfire, it can add an incredible experience to your wilderness adventure.

About the Author

CJ Wilson’s career in outdoor education has taken her from Maine to Minnesota, and from the Sierra Nevada to Patagonia. A long-time Outward Bound Instructor, she writes from her base camp in Asheville NC. When not writing, she might be found working as a ranger in a national park, bicycle touring or hiking her favorite trails near home.

OTHER POSTS YOU MAY LIKE

Read More

Read More

Read More